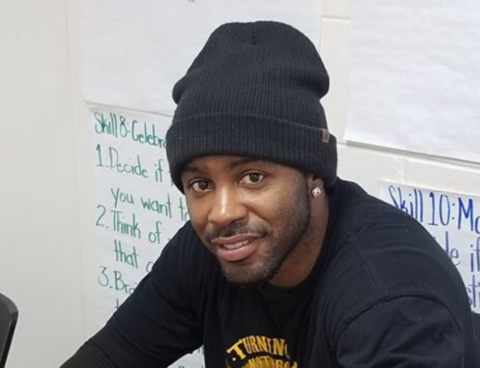

Winard has been a student at Turning Leaf for almost four months. He’s nearing graduation and I didn’t want his story to slip past me. After all these years, sometimes I have a sixth sense about the men I work for. Sometimes I feel that there’s a story to be told. I asked and he agreed without hesitation. Like every time I ask a student for their story, I explained that I would share it on social media and in our newsletter. “Are you good with that?” I asked. All good, he said.

I came into it cold. Before the interview, I didn’t know much about Winard other than reports from my staff and our brief interactions in the hallway and our print shop. I was blown away. The men at Turning Leaf are so resilient, and Winard is no exception. Had I faced the challenges he faced, I probably would have folded my hand years ago. But Winard and all the guys here continue to plug away, getting back up and putting the work in.

It was an honor to spend an hour getting to know Winard to document his story, and it’s my honor to share with you. I’m so glad I didn’t let this one pass me by.

Winard has a twin brother. It was his loyalty to that relationship which ultimately led him to prison. But, of course, it’s more complicated than just a brother’s loyalty. It’s also about circumstances: poverty, addiction, family, and abuse.

Most of my students’ childhoods are bad, but Winard’s is something most of can’t imagine, let alone relate to. He and his twin, along with his older brother and younger sister, grew up with their mom and dad in a trailer on John’s Island. They had neither power nor running water for five years. Winard’s dad was an abusive alcoholic, addicted to drugs and to gambling.

For food, the kids had whatever they could catch in the nearby creek – shrimp, crabs and fish. He remembers going to school and not understanding other family dynamics. Kids talked about fun things they did with their parents over weekends, vacations they were taking and things they were buying. Without a radio or TV, Winard had almost no access with the outside world. It took him longer than you would think to understand that his family situation wasn’t normal. He was teased and bullied in school. People knew what his life was like. Shame and embarrassment haunted him.

His older brother left their home at age 12. He called their grandmother and told her, “If you don’t come and get me right now, I’m going to disappear and you’ll never see me again.” She got him. Three years later, Winard, his twin, and his sister did the same thing. They left the trailer, went to a friend’s house and called the police. Winard and his siblings joined their brother to live with their grandmother.

Despite his circumstances, Winard didn’t get into trouble as a child or a teen. He wasn’t rebellious. He wanted to buy things and understood that working was the path to what he wanted. He and his twin brother worked at Burger King for five years. Bu then, when Winard was 21, their grandmother died. Everything changed.

Winard and his siblings went to live with his mother, who was by then living in North Charleston. “It was the major turning point my life,” Winard said, “If I had stayed in the country, I don’t think I’d ever have gone to prison.” His new neighborhood wasn’t great. People loitered on street corners where open-air drug dealing happened. Most people in his new circles lived a criminal lifestyle. Men made money quickly and had women, cars, and the respect of their peers.

The distance to Burger King made keeping that job impossible. Winard quit. For a while he tried to stay out of the streets: he worked various jobs, but keeping them became a hassle. People around him made quick money on their own schedules without a boss telling them what to do. The lure of the criminal lifestyle was strong. Winard’s twin brother already had already jumped in, but Winard still only dabbled on the fringes.

One day his brother dropped by his house. The police had been following him, suspecting him of selling drugs, and they came into Winard’s apartment looking for him. They found drugs on his brother, and both men were arrested. At his brother’s request Winard agreed to tell the police the drugs were his, in order to save his brother from getting in trouble. At 24, Winard had a criminal record.

Afterwards, he started having problems finding work. A criminal record will do that to a guy. When he did find a job, it was for less money than before. He went to prison for chronically driving on a suspended license. When he came out, he had an even harder time finding a job, for even less money. It was a downward cycle. He gave up the job search and sold drugs full-time.

But Winard’s full-time drug dealing wasn’t anywhere close to his brother’s level of criminal involvement, which included burglarizing houses, cars, and hoarding stashes of cash. He asked Winard to live in one of his houses to keep an eye on it, since he didn’t spend much time there. His brother also bought him a brand-new car. Six weeks after Winard moved in, his brother was arrested for a string of robberies. Winard was implicated, and eventually arrested.

The federal government offered Winard a deal. They weren’t really interested in him: he didn’t have an extensive criminal record, and they knew he wasn’t involved in the robberies. They just wanted details of his brother’s activity. They told Winard, “Your brother says you sold drugs for him. You knew about the cash in the house. You knew he bought you a car with illegal money. We can arrest you for that.”

But Winard was certain his brother wouldn’t rat him out. He denied knowing anything about his brother’s illegal activity, and for three years he sat in county jail, awaiting trial. He was facing 25 years.

On the day of his trial, he still didn’t believe his brother would testify against him, but his brother did it to save himself. He was facing 70 years in prison. His testimony against Winard meant that he only got 25 years. Others implicated in the crimes also testified against him to save themselves. Winard was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison.

If Winard had come clean about his brother’s illegal activity and not gone to trial, his brother wouldn’t have had the opportunity for a reduced sentence. Winard’s loyalty saved his brother from life in prison.

I asked him if he would have done it differently. If he could go back, would he have told the truth to save himself 10 years in prison, but at the cost of his brother’s life? “Yes,” he said, “100%.”

Winard was released from prison in November of 2019. He knew he wanted a new life for himself, but after ten years in prison he didn’t know who to ask for help or where to get a job. A few days after his release he went into a barber shop and saw a flyer on the wall for Turning Leaf. He decided to give the program a shot and never looked back.

What are his plans now? His time at Turning Leaf is ending. His goals are to find a good job and make up for as much lost time as possible. He has two daughters. Re-establishing those relationships are his priority now. He’s taking life one day at a time and using the skills he learned at Turning Leaf to make good decisions and be the man he always wanted to be.

Story Captured by Leah Rhyne