Van was the kid in his neighborhood who was supposed to get out. The smart one. The one everyone rallied around and protected. But somehow, still, at 17 he made a mistake, which led to another, and another, until he wound up deep in the exact life he was supposed to avoid: the life of a drug dealer and addict.

Today he’s using those experiences to help others find a new path the same way he did: through hard work, introspection, and a willingness to change.

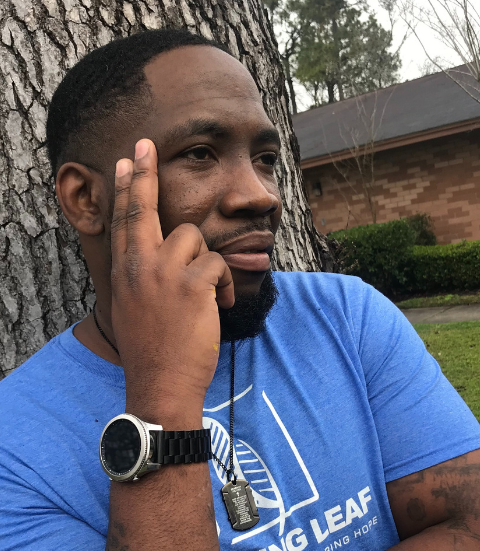

This is Van’s story.

* * * *

Van is acutely aware of the stories of the students in his class with Turning Leaf. “I didn’t have it anywhere near as bad as some of the rest of the guys,” he says.

But really, who’s the judge of that? Like so many of our students, Van’s childhood was marked by trauma and violence. His maternal grandparents were killed by his mother’s ex-boyfriend before he was born. He lived with his mother and great-grandmother. His father wasn’t really in the picture. A recovering drug addict who relapsed, he committed suicide when Van was 17 years old. They weren’t close, but considering 17 was the age at which things started to fall apart for Van, it’s safe to say his father’s death had a dramatic impact.

As a child, his neighborhood was filled with drugs, dealers, and the violence inherent in that world. Van was protected, though, and not only because everybody knew he was a bright kid destined for bigger things. “The whole neighborhood knew my mom,” he says, laughing. As in: they were afraid of her, afraid of what she’d do to them if they let anything happen to her boy. It was a good kind of fear.

In high school Van wrestled and had scholarships waiting for him when he graduated. He started smoking marijuana, though, and a drug bust at 17 landed him in hot water. He was expelled, his scholarships rescinded. The high school administrators encouraged him to take a year off, take some classes at Trident Tech, and then come back the next school year to finish school. Van had other plans.

He started selling drugs. “I thought, ‘I like to smoke weed, so why not sell it?’” he says. His habit and his sales stayed recreational for a few years, “but then I started having kids.”

After the birth of his first daughter, a friend said, “You know a lot of people, why don’t you get rid of this for me,” and handed him a bunch of cocaine. He sold it, bought more, and sold more. Money came fast, and so did more kids.

In his early twenties Van got arrested, sat in county for a while, and realized he should get out of the lifestyle. He worked a straight job for a few years, but when he and his children’s mother broke up, “child support started catching up with me.” He went back to what he knew, this time selling harder drugs like meth and heroin. He started using harder stuff, too. The lifestyle was exciting: women, drugs, and partying. A friend taught him how to print counterfeit money, so he added that to his repertoire.

Life was spiraling out of control, but Van couldn’t see it. Not yet. He was getting arrested for minor charges like possession, driving on a suspended license, and assaults and batteries for bar fights. “I had some anger management problems,” he says. But as the charges piled up, “it was nothing that made me say I’ve got to stop and slow down.”

That started to change after he caught his first felony charge, possession with intent to distribute cocaine, meth, and heroin. He was able to bond out, and friends told him to slow down. In Van’s mind, though, he’d just spent a bunch of money and had to make it up. “I probably should have stayed in jail and sat,” he says now.

A couple months later, he was arrested again, this time for trafficking, a far more serious crime. It landed him a $250,000 bond that kept him in jail, but not out of trouble. While he awaited trial, he met a guy who showed him how to counterfeit better. “When I get out of jail, I’m gonna do this,” he thought. “It’ll be great.” He had big “street dreams,” and when the charge resulted in ten years’ suspended sentence with five years’ probation, he thought he was sitting pretty.

His plan was to make enough money to get himself back on his feet, but when he got out he found his family in disarray. Three of his kids were staying in hotel rooms with their mom. “I felt like they needed me,” he says. “I felt like I had to do what I had to do.”

Things moved quickly from there. The counterfeit built up his bank account, and he started selling a lot more drugs. “I started using a lot more than I did before, too,” he says. “I’m making all this money but I’m also getting high all the time.” His relationship with his children’s mother deteriorated. He started talking to another girl, and she asked him to help her and a friend improve their counterfeit skills. He did, not knowing the Secret Service was watching her friend, capturing pictures of them and Van in his hotel room.

The street life started closing in. He ran into a high school friend right after using fake money in her store. She called the police, and when she warned him on Facebook messenger, he blocked her.

A couple of days before Christmas in 2018, Van was running out to pick up a new iPhone for his daughter when a friend called, wanting meth. It was late and Van didn’t want to bother with the deal, but the money was too good to turn down. This time he had a friend drive so he couldn’t catch another charge for driving on a suspended license.

When cops pulled up behind them, the friend sped up, allowing Van to throw his drugs out the window. But they were caught, as you usually are. Van admitted to everything, taking the full charge to keep his friend out of jail. He went to Berkeley County jail.

A few days later the Secret Service showed up to talk to him. Soon it was all over the local papers: Van was part of an accused counterfeit ring. He was indicted on federal conspiracy charges.

Together, the charges and plea deals added up to Van serving approximately 30 months total in various jails and prisons. “My daughter was crushed,” Van says. “That’s the part that hurt me the most.”

Today, he admits that going to prison was the best thing that ever happened to him. While inside, he started going to a DAODAS program, which provides services to addicts. He attended AA meetings. “At first I only went there for the microwave,” he says. “But then, after a couple of months, I started listening to the stories being told around me, and it hit me: you know what? I’m a drug addict!”

At the time of our interview, Van has celebrated 11 months of sobriety, starting in prison and continuing after. He’s living in an Oxford House, a sober-living facility, and thriving there. He attends AA and NA meetings three times per week, or more if he feels like he needs it.

He found out about Turning Leaf right before his release and never had any doubts about applying. Between Turning Leaf, AA, and the books our case manager, Justin, gives him to read, he’s learning a ton, realizing how much of his own personality he hid throughout the years to seem “hard.”

“I like being around the other guys at Turning Leaf,” he says. “I see where I was, and I’m surrounded by people who want to change. I want to change. My situation could have been a lot worse than it was. I know that. It makes me appreciate my second chance even more.”

“We don’t have to be a product of our environment. We can be more than that. It sounds like common sense, but a lot of us aren’t taught that as kids. Life is 20% of what happens to you, and 80% how you react to it. I live by that now.”

* * * *

Van starts college next month, working toward a degree in counseling. He’s hoping to find a car soon so he can stop feeling like a burden to his children’s mothers. His is a big, blended family, and he cherishes every minute he spends with the kids, their mothers, and his newfound friends at the Oxford House and Turning Leaf.

Congratulations on how far you’ve come already, Van. We’re all watching to see how far you’ll go. We know it’ll be incredible.