There’s a scene in The Shawshank Redemption where Brooks, the elderly man who’s been incarcerated for most of his life and has just been released, sits in his rented room, head hanging low. He doesn’t understand the world around him. He left his friends – his only family – in prison. Despair is his only companion.

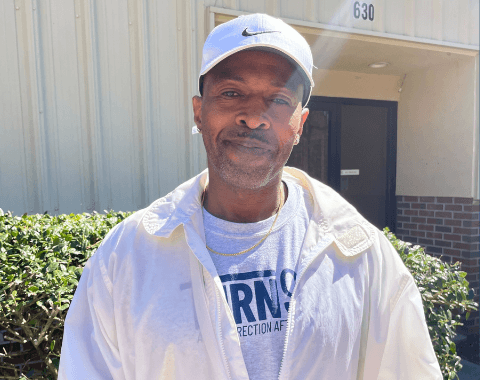

It’s impossible not to picture this scene when talking to Unk (short for “Uncle,” and so named because, for a while, he was the oldest man in the room in prison and in the Turn90 classroom). He served 25 years after his young adulthood spiraled out of control, and when he was released, regrets and despair waited with open arms.

Luckily, Unk found Turn90 and a path to, if not exactly redemption, at least a productive, happy life.

This is Unk’s story.

* * * *

Unk wasn’t always called Unk. Once he was Ronnie, a little boy growing up in and around Newberry, South Carolina, a small city just north of the state’s capital. The kind of place where no one locked their doors at night.

His home life was stable. Although separated, both his parents had good jobs and there was always food on the table. As a little guy, though, Unk says, “I was kinda bad. I liked to throw rocks a lot.” Normal kid stuff, but behaviors that were allowed to fester.

By high school, Unk found the wrong crowd. He hung with boys who cut class, bought beer, and drank all day. It was kid stuff, simple illicit pleasures, that led him to drop out of school in the 9th grade and live a life of…floundering.

He almost got his act together, once. He was in his early 20s, married, and living in Gray Court, near the mountains of Greenville. He had a job, a wife, a life. But the lure of the streets hooked him when he met a group of men who sold drugs and rolled with fast money, fast cars, and fast women. Unk craved that lifestyle, so that spring he took his income tax check, went to Greenville, bought some drugs, and started selling. “That was the biggest mistake I ever made in my life,” he says.

“I totally lost my mind,” he continues. “I was addicted as much to selling the drugs as the smokers were to smoking them. Fast money, jewelry, cars. Women throwing themselves at me. Being able to spend money at the drop of a hat.” There were no rules and no limit to the things he would do.

He started drinking, a lot, the alcohol addiction making him more reckless. He started catching charges, doing little bids in jail, getting out, and starting all over again. You have to be tough to be in the lifestyle, ready for anyone and anything who may be coming after you to take your money or territory. “I kind of wound up being a bad person,” he says. “Money was my only concern. Well, that and taking care of my mom, my son, and the guys who worked for me. My nephew was my lieutenant, and I always made sure I took care of the people who mattered to me.”

What followed was a chain reaction so bad, it’s hard to believe so many things could happen to a single person. Just a few short years – that’s all it took for Unk’s life to go completely off the rails. The stories from those years are cinematic and scary. They include:

Unk didn’t have a license but drove all the time, often while under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Once he passed out at the wheel and woke up in a hospital bed. Turns out he’d run his car off the road, crashed into a ditch, and was thrown into the windshield and back out the other side. The car flipped, landing on top of him, burning the side of his face and arm so severely that, when his ex-wife and her sister came to see him, the sister exclaimed, “That’s not him. That’s not Ronnie.” He had to heal in jail, changing his own bandages on weekends when the infirmary staff wasn’t around, and by the time he finally saw himself in a mirror, he cried, unable to believe what he saw. Both eyes were swollen, almost shut, with countless stitches. Burns so deep he bears the scars today. The police had told his mama he was dead, a memory that cuts him still.

When he got out of prison, he got right back in the game.

Another time, he almost accidentally shot his nephew, his right-hand man, with his sawed-off shotgun. His nephew was using the gun in the yard but it jammed. Somehow it went off in Unk’s hands, bullets launching into the space where his nephew stood moments earlier. He shot a hole in his mama’s wall and television remote control; he tried to hide the evidence but she found it anyway. He was, in that moment, a little boy afraid to get in trouble.

He stayed in the game anyway.

Once he sat in a neighbor’s yard for hours, drinking and selling drugs. The neighbor told him to leave, but Unc threatened the neighbor with his sawed-off shotgun. When the police showed up, he showed them his gun, too. “You’ve got to come with us,” the police officer told him. “We need to make sure there’s no bodies on this gun.” There weren’t – the gun was clean – and Unk went back home. There, the neighbor ran Unk down with his truck, hitting him twice then smashing him across the head with a crowbar. Doctors had to sew Unk’s ear back on.

Unk stayed in the game still.

The spiral was real, though. Paranoia set in. Although Unk was doing small bids of time, he always slipped through the cracks, spending way less time than he knew he deserved. The world closed in on him – probation officers, the city, the county, ex-girlfriends, men who wanted to steal his drugs and money. He ran from cops who weren’t even chasing him. He’d disappear for weeks at a time, booking a room in a hotel and refusing to answer the door or phone.

By the time drove into a drivers’ license check one night, he says, “I may have been begging to go to jail. I don’t know.” Survival instinct kicked in anyway. “I stomped it. I took off. I was a mess. Trying to roll a blunt, drink a beer, and outrun the police.” He almost ran himself over trying to intentionally crash the car while leaping out the door like you’d see in an action movie.

He hid in the house of a woman he barely knew. “Boy, what have you done,” the woman asked. “Everything is outside looking for you.”

It was true. Helicopters, the city, the county, dogs. The charges had finally all caught up with him. He knew he faced a big sentence.

“I was so relieved when I finally got caught,” he says. “I probably slept in the county jail for the first four months. Like a baby.”

He would eventually be sentenced to 25 years. “Man, I’m relieved,” he told a friend at the time. “I’m tired. So tired.”

The time passed in prison, as time tends to, and Unk finally grew up. He realized his lifestyle had to change. But when he was released, he came home to nothing. Everything he’d once had was gone, sold, pawned. He didn’t have anywhere to stay until his niece took him in. “She told me, ‘Unk, don’t worry. I got you.’ And she gave me everything I needed,” he says.

But he was hurting. Scared. It had been so long. He didn’t know how to be around people on the outside. “I started shutting down,” he says. “I kept pretending I was okay, but I’d go outside, hold my head in my hands, and cry. I even thought about going to bust a window just so I could go to jail for a while.”

Let that sink in. A man who’d been incarcerated already for 25 years (more like 30 if you count prior bids) was so overwhelmed by the outside world that he wanted to go back to jail.

Unk considers himself lucky that his probation officer pointed him toward Turn90. “I feel loved here,” he says. “I trust them. I don’t think I could have made it without going through this program.”

He’s learned from the classroom skills as well as the people around him. “I trust people again, and I’ve learned how to communicate.”

Unk is currently facing his next big transition: he’s about to graduate from Turn90 and start a job back in Newberry, where he can help take care of his mama. Unlike when he got out of prison, he says, “I’m not nervous. I’m like a little birdie. I’ve got to fly now. I’ve got to leave the nest. But Turn90 prepared me for this. I’m ready.”

* * * *

We know you are, Unk, and even if you’re a few miles away in Newberry, your Turn90 family will always be by your side!