The impacts of organized crime can echo through generations. In Emanuel’s case, it shaped his life so completely he wouldn’t be able to fulfill his dream of being a “square” until he was in his mid-forties.

This is his story.

* * * *

“I was nine years old the first time I saw a lady overdose from heroin,” Emanuel says. We’re minutes into our time together, and we’ve already discussed where he grew up (Greenville, South Carolina, in the same neighborhood as Jesse Jackson, with whom his mother went to high school), and what it was like (“a LOT of drugs,” he says, pulling a face). But this is the moment when I realize how different this story will be. Nine-years-old? He was a baby.

Emanuel and his five-year-old cousin had gone to a modern-day opium den, a “shooting gallery,” because a party had gotten a little crazy at their house. They went there sometimes to escape their own lives, and since their uncles were well-known drug-lords in the neighborhood, they were always allowed inside.

Even when a woman was dying. “She was sitting there with the life draining out of her,” he says. “And I was just stuck. I couldn’t even move.”

People tried to save her but she was beyond help. The boys were ushed into a different room. “And then he came to talk to us,” Emanuel says.

He, in this case, was the kingpin. The godfather. The man in charge of the neighborhood, in an American Gangster kind of way. “He asked us, ‘What did you see in that room back there,’ and even at nine, I knew enough to tell him we didn’t see nothing,” says Emanuel. Impressed, the kingpin handed Emanuel a fifty-dollar bill, and a twenty to his cousin. He drove the boys home in his tricked-out Mercedes with its gold bumpers and door handles.

“I put those fifty dollars away,” says Emanuel. “I wouldn’t spend it, wouldn’t tell anybody about it. The only one who knew I had it was my little cousin.”

He held onto the money until the next time the kingpin stopped in town. Emanuel ran up to him. “Man, I got something to show you,” he said. He was ten then, and eager to impress. He ran home and retrieved the bill, and once again climbed into the fancy car.

“What’s on your mind, young blood,” the kingpin asked.

Emanuel showed him the bill. “He tried to take it from me, but I wouldn’t let him,” says Emanuel.

The kingpin smiled. “You didn’t spend it,” he said. “Tell you what, give it to me.”

Emanuel did. In exchange, the kingpin handed him a hundred-dollar bill and five twenties. “He told me, ‘You put that hundred up, and you spend the twenties. But don’t spend the hundred. Next time I see you, I want to see the same hundred-dollar bill.’ I was ecstatic,” Emanuel says. “I had a Franklin!”

It was several months before the kingpin came back again, but when he did, Emanuel was waiting. “Boy, you done grew a little bit,” the kingpin told him. “Now, whatcha got to show me?”

This time the kingpin drove Emanuel to his house. He was thrilled when Emanuel showed him his treasure. He said, “You know, you have a responsibility. I can see you know it. Your uncles and I are pretty tight. I see they taught you real good. It’s time for us to take it to the next level.”

Emanuel was eleven years old and the kingpin gave him his first job. He began working after school, scouting for police on a street corner. He’d shout “Raids up” if the police were riding one way, or “Raids down” if they came from the other, and he made $70 each day.

The street lifestyle surrounded him. From a bootlegging grandmother to uncles who were lieutenants in local drug cartels, to parties at his house where he saw “piles of white stuff and green stuff” everywhere, the transition into the life was easy for Emanuel. It was all in the family, after all.

There were lessons to be learned, though. Emanuel was twelve the first time his uncle took him to New York City to do some Christmas shopping. His uncle said, “Never tell anyone when you’re going out of town or when you’re coming back. You never know what’s going to be waiting for you when you get back.” Emanuel didn’t tell his mother where he was going.

“B the time I was 13, I had my own crew to help me run things,” he says. By 15 he had his own car and motorcycle. He taught other kids the ropes. His transformation to child gangster was complete.

Or was it?

Emanuel felt a little different. He was a little quiet. Artistic. One of his paintings was chosen for a prize at a local church. It was later auctioned off and sold. In middle school he joined band and fell in love with music – first the clarinet, then the drums – the high school band director saw his talent and passion. “He said, ‘Emanuel, listen. I want to give you an opportunity to go to college through a band scholarship,’ and I just thought this could be my way out. I wanted to know what it would be like to be a normal guy.” It wasn’t meant to be. An uncle interfered, telling the band director he needed Emanuel every afternoon.

Then came a major blow. The one person who could always convince Emanuel to take a break from hustling was his girlfriend, Marie. They were 15 years old, children in love. She was a calm, steadying influence on Emanuel until she was shot and killed outside a bodega in Boston while visiting her grandmother. “After that,” he says, “I hit the streets with a vengeance.”

“I been shot, stabbed, run over, kidnapped. I been through a lot of things,” he says. He’s been to cocaine parties in Miami; made drug deals up and down the Eastern seaboard. He had an international driver’s license and used it around the world. He learned to test the product (drugs) he purchased before selling them on the streets. “If you put out bad work, people die,” he says.

He’s been arrested up and down the East Coast too. He spent a year in juvie in New Jersey. Six months in jail in North Carolina. Three in Virginia. And over 14 years total in and out of prison in his native South Carolina.

In 2018, Emanuel knew he wanted to do something different. He moved to Charleston and started working at a salon (he’s always cut hair – see above re: artistic and talented) and got a job doing maintenance at a local hotel. He did everything right, from immediately telling the HR woman about his past to overhauling the maintenance shop to training the new guy who started shortly after him. So when the HR woman told him the hotel’s corporate office was making her fire him, he was crushed. “I thought I was welcomed back to society,” he says. “I thought I was going to get to be a regular guy with a regular job. But after that, I thought I’m just meant to sell drugs. I can’t get a job because of my record. What else am I supposed to do?”

He fell right back into the incarceration cycle.

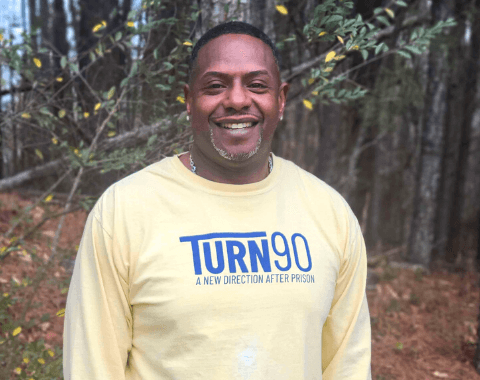

By the time he heard about Turn90 in 2020, Emanuel was out of jail but facing a significant charge: it was his third offense, and if convicted there was a good chance he’d be sentenced to life. Emanuel interviewed at Turn90 Columbia and told the program manager, Sarah, about his pending charges. It’s a long-standing rule at Turn90 that you cannot have pending charges to be in our program, so at first, he was told no. Another crushing blow.

But sometimes rules are made to be…well, if not broken, then at least occasionally amended. Emanual’s story stuck with Sarah and our executive director Amy, and Amy made the decision to hire him.

The experience has been life-changing. “I’ve learned so much with the 25 and 9,” he says (referencing the 25 social skills, and the nine ways to apply them). “The classes help you to be management material. They make you able to manage a company, a floor, a team. They teach you how to be a leader.”

Emanuel’s hard work helped him in court, too. When presented with information about Turn90 and letters of support from Sarah and Amy, the judge in Emanuel’s case made a choice. He suspended Emanuel’s sentence. “Pay the fines you owe and you’re a free man,” he told Emanuel. “Go back to Columbia, work hard, and keep moving on with your life.”

That’s exactly what Emanuel is doing.

“Turn90 has my back 120%,” he says. “I’m so grateful to be involved in a program like this. Turn90 has really turned my life ninety degrees– the right way. I’ve got some of the very best people I’ve ever met surrounding me, and they offered me a lifetime support system. You’re part of something bigger than yourself when you’re a part of Turn90.”

In the future, Emanuel hopes to build a nonprofit of his own, helping differently-abled people who have maybe reached the ends of their ropes. “Maybe my voice and story can help change someone else’s life,” he says. “I want people to know somebody out there cares. I want to serve.”

* * * *

Emanuel, you finally have the opportunity to live a “square” life, as you like to say, and you want to use it to help others. We’re unbelievably proud of you, and we can’t wait to watch you succeed beyond your wildest dreams!