Drugs. Robberies. Guns. Violence. There are so many things for parents to worry about. Sometimes, all a mama can do is try her hardest and hope that someday her child will hear her.

That’s how it was with Rigg. His mama did everything she could to show a good way to live. But from the moment he, as a little boy, touched a hot stove just because his mama told him not to, it was clear Rigg would make his own choices, whether or not they were the right ones.

It took a while, to be sure, but after years stuck in the incarceration cycle and even more years running the streets, Rigg is finally ready to listen to his mama.

This is his story.

* * * *

Rigg grew up in the Liberty Hill neighborhood of North Charleston in the 1980s. Most residents were property owners and lived the straight and narrow life. The community was tight. Everybody was related to everybody else.

“We were a single-parent household, but my mama was a hell of a provider,” he says. He and his three siblings never went without a meal. The lights were never turned off. She worked cashier jobs and was always able to make ends meet. They lived in rental properties when he was a kid but she owns a home today, a fact he mentions with obvious pride.

But Rigg was a handful. “Out of all my mama’s kids, I might have been the smartest one,” he says. “But I do the dumbest things. I just always wanted to get out there to see things for myself. I was always going to do exactly what my mama told me not to do.” Case in point: the hot stove. “She told me not to touch it, but I did. Then when she came out, I said, ‘Mama, I touched the eye, but it didn’t burn me. It just depends on how long you touch the fire, whether you get burned or not.’”

It was the late 80s and early 90s, at the height of the crack epidemic. Rigg saw enough in his neighborhood to burn him. Liberty Hill had more than its share of drugs and violence. Dealers, too, whom Rigg idolized. “I’d see someone on the streets, and I’d think, damn, he’s got all the nice shoes, the nice clothes. One day I’m gonna be him,” he says.

He and his family moved to a “better” neighborhood when Rigg was a teenager. There, he found a group of kids who also liked pushing boundaries. It began with robberies and slid into drug sales. They started making money – more than his mama could give him – and it became an addiction. He brought weed into the house one night, hiding it in his pillow while he slept. “My mama’s got a nose like a dog,” he says. She came into the room he shared with one of his brothers and zeroed in on the hidden goods. She grabbed him, said, “I know you didn’t bring this into my house,” and, in Rigg’s words, they “had a falling out.” He moved out and began staying with various friends. Life slipped rapidly out of control.

Riggs went to prison for the first time in high school. He pled a carjacking charge down to a strong-arm robbery and received a Youthful Offender Act (YOA) sentence of 1-6 years. He only served ten months, but then violated probation multiple times on drug and gun charges.

Research has proven over and over again that most people eventually age out of crime. They get too old, too tired to keep up on the streets, and they find other ways to live. Rigg was almost an example of this. When his son was born, he kept running the streets full-time, undeterred, but when his daughters were born, everything changed. “The way these little girls gravitate toward me,” he says. “I knew from the start: these girls cannot be without me.”

He started pulling back from the streets, ever so slightly, managing to stay out of trouble for a long time. As he entered his late 30s, Rigg wanted to transition completely away from the streets, but he knew it would be difficult. The streets were where he’d always made his money; he didn’t know how else to support his family. He enrolled in a free masonry class, but then disaster struck. He was caught with guns in a neighborhood rife with unsolved violent crimes and murders. The local police turned him over to the feds. A 40-month sentence sent him to Coleman Federal Penitentiary in Florida, which has housed some notorious prisoners including Al-Qaeda supporters and Whitey Bulger.

It was a wakeup call. “That’s where I learned to respect life,” he says. “The first day I was on the yard, I assumed everyone was in for a similar time and similar charges as me.” A man approached him and asked Rigg how long he was in for. “I said I got forty, and he replied back to me I got forty years too! It really opened my eyes. Some of those dudes had nothing to lose, and I’m in there just trying to make it home.”

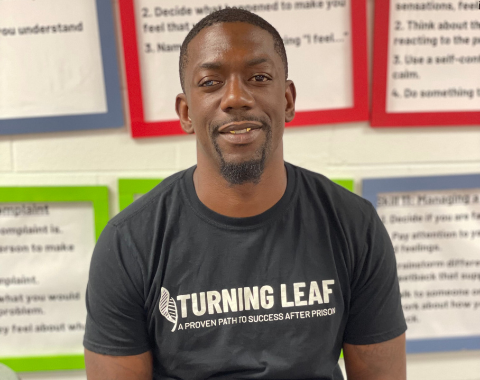

Which he did, after serving 29 of his 40 months. Several chance encounters landed Rigg at Turning Leaf, where he is continuing his transition away from the streets. “The only way to change what’s going on around me is to change myself,” he says. And while he thinks he’d have been successful in leaving the streets behind if he’d finished his masonry class several years ago, he’s grateful for what he’s found here.

It wasn’t love at first sight, though. Let’s be clear on that. “I was kind of resistant at first,” he says. “The program was taking up my whole day. By the time I’d get off everything was closed and my kids were tired.”

Rigg had a turning point when the Classroom Facilitator, Winard, opened up to him about his own life and experiences. Rigg says, “When he let me know who he was and what he went through, I realized everybody in the classroom is the same as me, even the teacher. You can’t tell what his life was by looking at him. He keeps a smile on his face and he’s clean cut and all that. But he really understands where I’m coming from.”

Rigg also found support from the Case Manager, Justin. He’s found all the people at Turning Leaf, in fact, to be genuine. Kind. Supportive. He knows a program like this is only as good as the people running it, and he believes Turning Leaf is great.

He uses Skill #5, Deciding to be Responsible, daily. “It always comes down to that one decision,” he says. “Deciding to do the right thing might be a little harder, but in the end it’s going to pay off.” He discusses the day’s lessons with friends at night, and reflects on his journey when working on his homework. It’s almost like his life has come full circle, and he’s finally learning the lessons about hard work, and dedication that his mama tried to teach him all those years ago.

* * * *

Rigg is leaving us very soon to go to his permanent job, but we know he’s going to succeed, using all the skills from the classroom and all the wisdom he’s earned through a life full of twists and turns. Best of luck to you, Riggs! You’ve got this!