-By Leah Rhyne

Is the American Dream still a thing? Can someone still pull himself out of poverty with hard work and dedication?

Or is that dream dead?

If ever a Turn90 student story makes you wonder, it’s this one. Solo’s parents did the right things. They worked hard. They instilled values in their children, teaching them right from wrong.

It wasn’t enough to keep their son safe. Despite their best efforts, he believed he had no option but the streets. He was arrested a whopping 24 times before finding Turn90. He’s spent over a decade in prison. He always wanted out but never knew how.

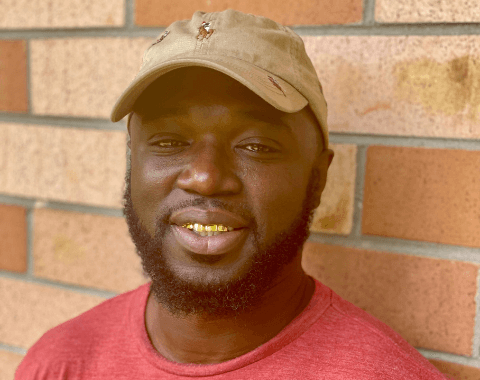

This is Solo’s story.

* * * *

“Some friends gave me my name,” says Solo. “I’d isolate myself from the group a lot.” It’s no wonder he did. Born on the west side of Charleston in the early 1980s, he lived in 15 different neighborhoods before turning ten years old. His parents worked long shifts at low-paying jobs, leaving Solo and his three sisters in the care of his grandmother. They never quite made enough money, though. Unpaid rent sent them from place to place, and each time the kids had to find a new life. “I became protective of myself and my sisters,” says Solo, the second oldest child and only son. “I didn’t know who to trust or who was going to be there for me or who was out to get me.”

He loved basketball, practicing on neighborhood courts long after dark. “I remember playing basketball at three or four in the morning,” he says. “People used to ask me why I wasn’t in the house.” With his parents’ long hours and multiple jobs, he had a lot of time to be out on his own, whether they knew it or not.

But that’s not to say the projects were safe. Far from it. When Solo was eight years old, he was walking to a house party on Halloween with his mother and sisters. A car rolled down the street and opened fire. He froze. Risking her own life, his mother ran back and pulled him to the ground. “I didn’t know what was happening. All I heard were the shots. Then as the car rode off, people on the corner in front of me were getting up. Someone was shot. That was the first time I ever saw someone get shot.”

Notice he doesn’t say it’s the last. Solo is protective of his trauma. What’s unsaid is louder than what’s spoken.

“I didn’t know how to feel about it,” he says. “All I knew was that it wasn’t right. I knew right from wrong. Being where I was from, I didn’t know if this was normal, but I knew it wasn’t right.”

The family moved to North Charleston soon thereafter, and it was the same game in a different setting. Being accepted was everything to Solo. Basketball helped, and then in the eighth grade, he says, “things started to go left for me.” He’d always been a good student, making A’s and B’s through elementary and middle school, but life had begun to change. His new friends skipped school. Most sold weed; some sold crack. Solo saw an opportunity. “I was tired of living without what other kids had. When I found the people who wanted to accept me, and they were doing these other things, I thought, well, maybe I’ll be accepted if I do it, too.”

He began selling weed and skipping school. His first arrest for selling marijuana came when he was only 14 or 15 years old. Sent to juvenile hall for a night but released the following morning, the arrest had little impact on him. “It didn’t faze me because I got right back out,” he says. “The fellas I was hanging out with, we had one thing in common. We didn’t have anything, so we had nothing to lose. I think that’s what led me to push my luck.”

Solo began skipping school more and more. He learned a lot in those early days, like that the early bird gets the worm in the drug trade. He was always the first one out and often the last to leave. If he wasn’t on the streets, he was losing business to someone else.

Could anything have stopped him? Solo thinks maybe if his dad had been physically present, he may not have turned to the streets. But he’s quick to note he doesn’t blame his father. Not at all. His father was trying to do right by his family. “He just didn’t have the opportunity to be the role model I needed him to be,” says Solo. “Years later, though all the arrests and prison time, he was always the person who was there for me. But I do think he’d have been able to stop me if he didn’t have to work so much. He’s a firm person and follows through on what he says. But having to make threats over the phone to me didn’t work. I wasn’t scared. I just thought, ‘You’re not there,’ and I did what I needed to do.”

What Solo needed escalated when he became a father at age 16. “Being a 16-year-old expecting a baby is basically like…you’re a baby, having a baby,” he says. “You wind up growing up early because even though you’re a teenager you made an adult decision, so now you have to stay and play the part.”

For Solo, playing that part meant increasing his presence on the streets, as well as varying his products. The guys around him who sold weed were making pocket change, but the ones selling crack, he says, were making a killing. They were the ones with the fancy cars, the jewelry, and who had the ability to support their families. “That’s what I wanted,” he says. “I needed the money. I didn’t have time to play anymore.”

His goal was clear: Solo wanted to make enough money so he didn’t have to sell drugs anymore. He always sought a way out. “I had a good upbringing,” he says. “My parents worked hard. I knew what I was doing was wrong, but in a sense, I also thought I was helping all of us.” He gave his mom and sisters money when they needed it and provided for his baby. “I had a good conscience, and I came from a good family. Circumstances led me to do the things I had to do.”

Life on the streets wasn’t all it was cracked up to be, though. Solo saw a lot in those years. Guns (yes, after being robbed a few times, he always carried a gun), violence. Gangs and other dealers fighting for territory. Women prostituting themselves for money. The neglect inherent in the lives of the addicted: mothers and fathers, high, walking the streets with small children at their sides, all day and all night. It was bleak.

Trouble also followed close behind him. “When you’re on the streets, working hard like I was, you start to get noticed,” he says. In North Charleston, he found his turf, but being there daily made him a target. “I had to be out there for my kids, day in and day out, but that’s when the arrests really started.” Once they started, they kept coming, back-to-back-to-back. Some were for simple possession, tickets he beat easily, but with time the charges escalated.

His first sentence came when he was 23 years old. He was sent to the Shock Incarceration Program, a 90-day alternative to prison boot camp. In his last month, he got into a fight and was sent to prison for an additional ten months.

When he got out, he hit the streets even harder to make up for lost time. There, trouble continued. Arrests continued. His sentences grew longer and longer. “My record was starting to pile up,” he says. “Things went wrong, just like everything in the streets goes wrong.”

After a five-year sentence he got a straight job, but here’s the thing: he’d kept on having more kids through the years. “Being in jail makes you want to have another kid,” he says, laughing. “I’d be gone for a minute and here it is, I’ve got another kid.” The job he was working couldn’t support his growing family, so he returned to the streets, again and again.

Finally, the end came: a federal indictment put him away for six years, and Solo found a way out. He found Turn90. He couldn’t believe it at first. “I never thought something like this could exist,” he says. “An opportunity for a felon to come home and get a job, with job placements where you have an option to pick and be comfortable in the type of work you’re doing? And if you don’t feel like your first job is the right fit, they help you find another one? Could it be real?”

At Turn90, Solo finally found his way off the streets that held him captive all those years. And while he came for the job support, he loved the classes, too. “They play a good part. I got to work on my people skills, to hone in on the place where I fit with jobs, my kids. It really helps to know how to stay calm and collected.”

He graduated from Turn90 a few months ago. The first job wasn’t the right fit, so, as promised, Justin is helping him find something else. He’s back in the Print Shop until the perfect job comes along. His presence is calm and quiet. He’s been helping another program participant study for the GED.

And when asked what else he wants people to know about him, he says, “I come from the same struggle that any Black man in America comes from, but there’s always room for change. There’s also always an opportunity out there for you. You just have to be willing to find it and do a lot of listening, instead of thinking you know everything. Everybody needs help sometimes. You have to listen and learn, or else you might miss an amazing opportunity.”

* * * *

We’re so glad you didn’t miss this opportunity, Solo. And when your plan to own a fleet of trucks and run your own business pans out, you just may restore our faith in the American Dream. After all, we all have our own origin stories…but it’s how we shape our futures that matters in the end.