At 24 years old, Alizé is younger than most of the guys we see at Turning Leaf. A lot of times, guys younger than 25 struggle with the program. They’re youthful, still impulsive, and not quite ready to say goodbye to the streets.

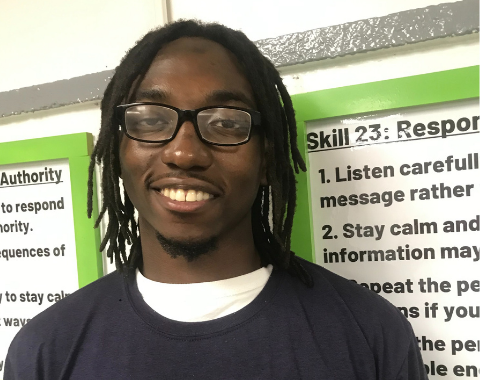

It’s different for Alizé, though. A quiet man with a polite smile and a “yes, ma’am” from beneath his mask in the hallways, it’s taken me a minute to get to know him. But in the classroom, he’s a calming force, always doing what’s asked and more. He’s been to prison and come out on the other side determined to be a better example for the two people who matter most: his little brother and sister.

This is Alizé’s story.

* * * *

Alizé grew up in North Charleston. He knew his dad a little but didn’t actually spend time with him. It was just Alizé and his mother and then, after a few years, his little sister, and a little brother a few years after that. They lived with his grandmother, but Alizé knew his mother wanted a place of their own.

The most positive role model in his life was Alizé’s granddaddy, who had his own story. “My granddaddy was a bootlegger,” he says. “A liquor man. You come over there, you buy liquor, buy cigarettes, blunts, cigars. Candies and chips. He had a little bit of hustle.” He had diabetes, and was an amputee which, according to Alizé, kept him from “straight” work for the rest of his life. So while he was loving and cared for Alizé, he wasn’t exactly modeling great behavior for a little kid desperate to help his mama out.

“I was trying to be the man of the house,” says Alizé. “I was looking up to the wrong people, not listening to my mama. Seeing her struggle, I wanted to help, but I was too young. The only way I could see to help was to go out and try to hustle.”

He was 11 years old the first time he smoked marijuana. He’d grown up watching his cousins and other guys in his neighborhood. “I had a lot of family tied up in different things,” he says. “I didn’t have a real father figure so when I went outside I was trying to run around and be like my older cousins. And instead of pulling me on a different path, they put it in my hands.”

At 12, Alizé was dealing. He says, “My mama stayed on me as much as she could, but there’s only so much she could do. She had to worry about my brother and sister.” He was trying to help, but now he knows, “even though I was helping her financially, I was hurting her mentally and emotionally. She knew what I was out there doing.”

He stayed in school until the 9th grade when he was expelled for truancy and fighting. He was full-fledged in the street life from then on. “I might be up all night and sleep all morning,” he says. “I’d get up late – about one or two o’clock – with a bunch of missed calls. I’d catch up, go make plays. I’d make sure my gun was with me all the time no matter where I’d go.”

He’s had to use the gun but doesn’t like to speak about it. It was an integral part of him, though. A piece that could literally never be left behind. “Once you get a little bit of money,” he says, “people get jealous and they might try to rob you. Or somebody might have a problem with someone in my clique, or they might see me and try to get at me. The gun is mandatory. You gotta keep it on you.”

Somehow Alizé stayed out of trouble with police until he was twenty, when the feds caught him on a drug trafficking with possession of a firearm charge. “I had a feeling about the informant I served when I did it,” he says. “But they waited so long to get me.” The sale went down in 2016 but they didn’t arrest Alizé until October of 2017.

That day, he was with his granddaddy, helping to take care of the older man. “I got up early that morning to go over there, get him up, wash him, fix him something to eat and get him together,” says Alizé. His granddaddy knew what he was doing with his life and didn’t approve, but that morning Alizé was in the back room anyway, sealing up some dope, getting ready to make a play. Suddenly, he says, his grandfather called, “’Man! Man!’ He called me Man. ‘The police are outside,’ he said.” Alizé thought they were just riding past, that his granddaddy was exaggerating. “But when I looked out the window, I saw the FBI and the sheriff’s office, and I knew they can’t be here for my granddad.”

They weren’t. The feds had finally caught Alizé.

He sat in county for about 15 months before pleading out to a five year sentence. “Prison and jail are different things,” he says. “In jail I was more laid back. I knew a lot of people there. I was just waiting, trying to see if I’m going home or if I’m going up the road.”

“In prison,” he continues, “you can’t let nobody think you’re soft or try to play with you in any type of way. You have to stand your ground.”

He was part of a race riot early in his prison stay. Blacks and whites fought each other, and while a lot of people “got messed up,” Alizé came away unscathed.

Eventually, he settled in and realized it was time to make a change. “I got in good with a couple of older dudes, trying to point me in the right direction. To calm me down. I’ve been really getting into the word of God,” he says. “I’ve been reading the Bible a lot.” He got a job in the movie room and found a way to be his laid back self again, just trying to stay out of the way.

His granddaddy died while he was still in prison. It was hard, but Alizé believes he’s in a better place now.

When Alizé was released from prison to finish his sentence in a halfway house, he knew he wanted something different. “I wanted to see a change in my life,” he says. “My sister is 17 and my brother is 12. They look up to me and, you know, my little brother, he’s been looking up to me for the wrong reasons. I’d like to see it rub off on him now that I’m back and things are better. Because he’s 12, and that’s the age I was when I got started. I can see him wanting to do things like that so I really need to set a good example for him. I don’t want him going down that path.”

“I also want to make a good life for myself,” he adds. “I want to have a family, a wife and kids, and I don’t want to be back and forth in jail for the rest of my life.”

It’s a great motivator for Alizé, as is Turning Leaf. His case manager at the halfway house told him about the program shortly after he arrived, and he called the next day. While the classroom was overwhelming at first (no one likes to roleplay in their first week, it seems like), he loves it now. “It’s a way to express yourself, for me to be myself,” he says. “It also helps you to think about stuff. It’s easy to get in trouble and hard to get out, but if you use the skills you’ll be all right.”

Deciding to say no has been a hugely important skill for Alizé. “I came home to a lot of people trying to get me to go down the wrong path,” he says. “They’re trying to put drugs in my hands, to put guns in my hands.” Setting boundaries helps, too. “I love some of them. We grew up together, but I have to distance myself sometimes.”

In the future Alizé wants to get his CDL and to get certified as a diesel mechanic. He smiles when he talks about the future. He has a plan, and for the first time he knows how to implement it. He knows he can get there. And he knows he’s on the right path.

* * * *

We know you’re on the right path, too. And we’re going to do everything we can to help you, Alizé. We’re so proud of you, and at 24, you have a lifetime waiting for you!